PM8 - Research Paper. Rozen-Bakher, Z. Do We Wrongly Use Equal-weighted Index between the Buyer and the Seller to Determine Cultural Distance in M&As? Analysis of Hofstede and Globe

Rozen-Bakher, Z. Do We Wrongly Use Equal-weighted Index between the Buyer and the Seller to Determine Cultural Distance in M&As? Analysis of Hofstede and Globe Research Paper, PM8. https://www.rozen-bakher.com/research-papers/pm8

COPYRIGHT ©2021-2024 ZIVA ROZEN-BAKHER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Rozen-Bakher, Z

Do We Wrongly Use Equal-weighted Index between the Buyer and the Seller to Determine Cultural Distance in M&As? Analysis of Hofstede and Globe

Abstract

Due to the mixed results of cultural distance in the current literature along with the struggle to explain the high failure rate of M&A strategy, this study takes a different approach by examining if analysis the national culture of the Buyer versus the Seller instead of analysing the cultural distance between the Seller and the Buyer may explain the unresolve risk of national culture when M&A strategy is implemented. The study used the Hofstede framework, as well as the Globe as a control framework. The sample is based on the accounting research method by analysing annual reports (10K) of 190 Sellers and 190 Buyers from 11 countries. The study revealed that the national culture of the Buyer more impacts M&A success compared to the national culture of the Seller. This finding challenges the use of cultural distance with an equal-weighted index between the Buyer and the Seller because of the dominance of the Buyer over the Seller. Thereby, the testing of equal weight between the Buyer and the Seller may explain the mixed results in the current literature. The study also indicates that exists a trade-off between the revenue and profitability regarding the six cultural dimensions of Hofstede, which may explain the high failure rate of M&A strategy. However, the study concludes that PDI and IDV of the Buyer more predict M&A success compared to other Hofstede dimensions. Future studies should explore the reasoning for the dominance of the national culture of the Buyer over the Seller in predicting M&A success.

Keywords: Firm Performance; Globe; Hofstede; Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As); National culture; Risk Management; Strategy

Introduction

The M&A literature mainly examined whether the national cultural distance (e.g. the composite index of Kogut &Singh, 1988 (Barkema et al., 1997; Brouthers & Brouthers, 2001) influences Merger and Acquisition (M&A) success (Bauer et al., 2016; Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Boateng et al., 2019; Brock, 2005; Gomez-Mejia & Palich, 1997; Lim et al., 2016; Morosini et al., 1998; Rozen-Bakher, 2018b; Slangen, 2006; Stahl & Voigt, 2008; Vaara et al., 2014; Very et al., 1997; Weber et al., 1996), rather than to examine how the national culture of the seller or the buyer affects M&A success. (e.g. seller’s PDI or seller’s UAI). The main problem with the current examination is that countless studies that explored the cultural distance did not succeed yet to give a clear answer if the national culture differences impact or not M&A success.

Considering that, there are two foremost reasons that may explain the unresolved risk of cultural distance in the existing literature. The first one is the Mixed Results between the previous studies (e.g. Angwin & Savill, 1997; Bailey & Li, 2015; Bauer et al., 2016; Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Boateng et al., 2019; Brock, 2005; Gomez-Mejia & Palich, 1997; Hofstede, 1980a; Huang et al., 2016; Kayalvizhi & Thenmozhi, 2018; Lim et al., 2016; Morosini et al., 1998; Norburn & Schoenberg, 1994; Olie, 1990; Rozen-Bakher, 2018b; Sarala, 2010; Slangen, 2006; Stahl & Voigt, 2008; Tang, 2012; Thomas & Grosse, 2001; Vaara, 2003; Vaara et al., 2014; Very et al., 1997; Weber et al., 1996). There are studies that showed that cultural distance positively impacts firm performance, while other studies showed negative impact, still, other studies showed no significant results (Huang et al., 2016; Stahl & Voigt, 2008; Rozen-Bakher, 2018b). Nevertheless, early studies even showed a change in the impact direction over time (Li & Guisinger, 1992; Loree & Guisinger, 1995), such as the study of Li & Guisinger (1992) that showed negative impact in the period of 1976-1980, while in the period of 1980-1986, most of the negative impact disappeared. This may suggest that the negative attitude of Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) regarding cultural distance was diminished as globalization has evolved. The second reason is the Methodology Differences between the previous studies. Most of the previous studies examined the cultural distance based on Hofstede framework (e.g. Brouthers & Brouthers, 2001; Rozen-Bakher, 2018b; Stahl & Voigt, 2008), still, other studies examined it based on the GLOBE framework (e.g. House, 2001; House et al., 1999, 2002, 2004; Tang, 2012). However, the problem with the methodology differences is not related only to the framework used but also regarding the cultural dimensions used in the studies. Many studies used the integrated index of Kogut and Singh (1988) that based on the four main cultural dimensions of Hofstede (e.g. Barkema et al., 1996; Benito & Gripsrud, 1992; Brouthers & Brouthers, 2001; Gomez-Mejia & Palich, 1997), while other studies used only one or two cultural dimensions of Hofstede or Globe (Alipour, 2019; Brock, 2005; Rapp et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2017). Given that, it’s unworkable to make a generalisation based on the current literature if cultural distance impacts positively or negatively M&A success (Brock, 2005; Stahl & Voigt, 2008; Rozen-Bakher, 2018b; Weber et al., 1996).

Regardless of the above, many M&As studies put emphasis on exploring the role of the Seller, rather than the Buyer with the aim of predicting M&A success. That is based on the due diligence idea that checking the Seller before the deal may reveal if the seller is worth the deal from the viewpoint of the Buyer. Thus, due diligence usually includes a cultural distance aspect in cross-border M&As. However, the M&A literature indicated that the due diligence per se may be complicated in cross-border M&As due to the physical distance/ culture distance (Bruner, 2004; Lajoux & Elson, 2000; Perry & Herd, 2004; Puranam et al., 2006; Rozen-Bakher, 2018e; Zaheer, 1995). Nevertheless, previous studies lack to investigate if the national culture of the Buyer per se has a role in predicting M&A success compared to the national culture of Seller per se, regardless of the examination of the cultural distance between the Buyer and the Seller. In other words, the option that the Buyer may predict M&A success more than the Seller was not examined in the current M&As literature. This investigation is particularly important due to the high failure rate of M&A strategy (King et al., 2004; Kumar & Sharma, 2019; Matsumoto, 2019; Renneboog & Vansteenkiste, 2019; Rozen-Bakher, 2018a, 2018c; Sarala, 2010; Steger & Kummer, 2007; Tichy, 2001; Venema, 2015; Thelisson, 2020; Weber et al., 2012) without giving clear explanations by the existing literature why the theoretical success of M&A strategy contradicts the reality of the countless failure of M&A deals. In other words, at the theoretical level, the principles of M&A strategy do not align with the reality of countless fail deals. Hence, at the theoretical level, M&A literature lacks to determine which factors or circumstances lead to a failure of M&A strategy, or vice versa, to M&A success. Although, the study of Rozen-Bakher (2018c) showed that M&A strategy leads to a trade-off between the revenue and the profit in the post-M&A period, based on the types of M&A, namely horizontal, vertical or conglomerate. Still, more studies are needed to determine which factors lead to a trade-off between the revenue and the profit when the M&A strategy is implemented, such as the national culture factor examined in this study.

In the light of the above, this study takes a different approach to fill the gaps in the current literature through investigating the role of the national culture of the Buyer vs. the Seller in predicting M&A success, rather than using the cultural distance, as illustrated in Figure 1. To achieve it, the study used the Hofstede framework to compare the national culture of the Buyer versus the Seller. More importantly, the study also used the Globe framework as a Control Framework to validate the results of the Hofstede framework with the aim of getting more clear answers about the role of the national culture in predicting M&A success. More than that, the comparing between the national culture of the Buyer versus the Seller may help to determine who is more dominant in predicting M&A success, the national culture of the Seller or the national culture of the Buyer.

The research paper is organised, as follows: The next section outlines the theoretical background and hypotheses. The following sections describe the methodology and present and discuss the results. The concluding sections present the conclusions and discuss the theoretical and managerial implications. The final section discusses the limitations of the study and gives recommendations for future studies.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

In this study, a research model was developed to explore the role of the national culture of the Buyer versus the Seller in predicting M&A success, as shown in Figure 2. The research model includes the six cultural dimensions of Hofstede Framework, namely H-PDI, H-IDV, H-UAI, H-MAS and H-LTO, while H-IVR serves as a control dimension, as well as the nine cultural dimensions practices of Globe framework that serve as control dimensions to validate the results of Hofstede framework, with the aim of getting a clearer understanding IF and HOW the national culture of the Seller vs. the Buyer affect M&A success, as discussed in this section below.

Alternative Analysis for Hofstede Framework in M&As: National Culture of the Seller versus the Buyer instead of Cultural Distance between the Seller and the Buyer

The M&A literature highlights the importance of exploring the cultural distance between the home country and the host country in cross-border M&As. However, this study chose a different approach by investigating the national culture of the Buyer versus Seller instead of the cultural distance between the Buyer and Seller, as illustrated in Figure 1. Thereby, this study should be considered as a pioneering study due to the comparison between the national culture of the Buyer versus Seller aimed at predicting M&A success.

National culture is defined as a system of shared values and beliefs that represent common mental programming (Hofstede, 1980a, 1991). The values and beliefs reflect the widespread basic concepts in a society that direct people in relation to various issues, such as what is considered as good or evil?, which subject important or not?, what obligations should be carried out towards society?, and more (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Hofstede, 1983; House et al., 2002). National culture also influences normative behaviour by defining the principles and values that guide the individuals within the social structure (Probst & Lawler, 2006; Triandis, 1995).

However, the national culture not only affects the behaviour of individuals (Probst & Lawler, 2006; Triandis, 1995) but also the behaviour of organisations in society (Hofstede, 1980a Gelfand et al., 2007; Tsui et al., 2007). The national culture affects organisations through the external environment, such as the values of the members of competing organisations, governments, and the public at large (Hofstede, 1980a). The values of the organisation's environment determine what an organization can and cannot do (Hofstede, 1980a). Therefore, the values of a host country affect MNEs' activities related to many topics, such as working values, level of trust and attitude to achievement and time (Hofstede, 1980b, 1983, 1993, 2001; House et al., 2002; Jalalkamali et al., 2016). For example, the working values could affect labour productivity via the willingness to work hard. discipline, and attitude towards bribery, while attitude to achievements could affect the competitiveness at work. However, attitude to time has an influence on the duration of decision-making and commitment for delivery, while the level of trust impacts the nature of agreements.

Hofstede developed a framework of national culture that allows comparing cultural values between different societies (Hofstede, 1980b, 1983, 2001, 2011). Hofstede framework is considered in the literature as the prominent cultural framework (Brock, 2005; Brock et al., 2000; Rozen-Bakher, 2018a; Sent & Kroese, 2020; Tung & Verbeke, 2010; Zhou & Kwon, 2020), still, there are studies that also used GLOBE framework (Globe-global leadership and organisational behaviour effectiveness) to examine national culture (House, 2001; House et al., 1999, 2002, 2004; Waldman et al., 2006) or even in both of them (Alipour, 2019; Chhokar et al., 2007; Shi & Wang, 2011; Xiumei & Jinying, 2011).

However, at the theoretic level, there is a similarity between Hofstede and Globe regarding most of the cultural dimensions of Hofstede. Still, there are studies that showed a negative correlation between Hofstede and Globe in relation to those dimensions with theoretical similarities, such as regarding the dimension of Uncertainty Avoidance (Alipour, 2019). Nevertheless, Globe introduced new cultural dimensions that do not have theoretical similarities with Hofstede, as presented in Figure 3. Therefore, the development of the hypotheses in this study is based on five cultural dimensions of Hofstede framework − H-PDI, H-IDV, H-UAI, H-MAS and H-LTO − as discussed below, while H-IVR of Hofstede and the nine cultural dimensions of Globe are served as control dimensions in trying to understand the unresolve risk of the national culture in M&As.

Hofstede-Power Distance (H-PDI). H-PDI represents different solutions to a basic problem of human inequality (Hofstede, 1983, 2011). This index suggests that a society’s level of inequality is endorsed by the followers as much as by the leaders (Hofstede, 2011). Control of human behaviour is necessary for organizations, and this can be achieved through the unequal distribution of power (Hofstede, 1980a). The distribution of power contributes to creating dominant coalitions, which define the organizational goals (Hofstede, 1980a) to achieve success. It also contributes to the shaping of the organizational structure and its formal procedures (Hofstede, 1980a). A high H-PDI reflects centralisation, a lack of consultation and autocratic leadership (Brock, 2005; Hofstede, 1983; Tayeb, 1988) where subordinates depend more on their managers (Very et al., 1993; Very et al., 1996), rather than themselves (Brock, 2005). In contrast, a lower H-PDI reflects independent subordinates, preference for consultation and bottom-up organisational structures (Brock, 2005; Hofstede, 1983; Very et al., 1993, 1996).

Considering the above, in a low H-PDI, subordinates are more likely to consider themselves as equals to their managers, so they seek equality in interactions (Huang et al., 2016). Hence, a lower H-PDI is supposed to improve cooperation between the Buyer and Seller, which is supposed to help to pass smoothly the integration stage without political infighting. Even employees’ participation (Khatri, 2009) is influenced by H-PDI (Brockner et al., 2001; Lincoln et al., 1981). A low H-PDI could help to obtain a high level of employees’ participation during the M&A process, particularly if it leads to a collaboration between the buyer and seller, resulting in improving M&A performance. Brockner et al. (2001) showed that employees with low H-PDI prefer a high level of participation compared to those with high H-PDI.

However, in high H-PDI cultures, hierarchy organizations are the norm, so lower positions follow orders and naturally respect higher positions (Huang et al., 2016; Gelfand et al., 2007; Tsui et al., 2007). Hence, in the case of a high H-PDI, the employees expect to be told what to do without taking too much responsibility(Khatri, 2009; Triandis, 1994). That is could help to remove obstacles during the integration stage because it minimises the political-infights, but at the same time, it may harm the profitability gain and synergy success due to a lack of collaborative behaviour between the buyer and the seller. That particularly applies when the employees say the expected thing with the aims of surviving in their jobs (Prendergast, 1993), especially if the managers would like to be surrounded by ‘yes man’, which may hinder the organisation’s ability to benefit from the experience and knowledge of subordinates (Khatri, 2009), resulting in a failure of M&A. Given that, during the integration, employees may react to the new hierarchy of M&A according to their H-PDI (Sarala & Vaara, 2010; Teerikangas & Very, 2006), namely in case of low H-PDI, they value equality, while they value hierarchy in case of high H-PDI . (Huang et al., 2016). A high H-PDI could also lead to ineffective communication because communication takes place vertically downwards, and informal and horizontal communication is quite limited (Khatri, 2009), which could negatively influence the whole M&A process.

Hypothesis 1: A higher H-PDI has a negative effect on revenue and profitability between the pre-M&A period and the post-M&A period.

Hofstede-Individualism versus Collectivism (H-IDV). H-IDV refers to the integration of individuals into primary groups (Hofstede, 1983, 2011). Individualists are motivated by their preferences and needs, with priority given to their personal goals, rather than to the group goals (Robert & Wasti, 2002; Triandis, 1995). Conversely, collectivists view themselves primarily as parts of a whole, such as a family, a network of co-workers, a tribe, or a nation (Robert & Wasti, 2002; Triandis, 1995). Collectivists are mainly motivated by the norms and the duties imposed by the collective entity (Robert & Wasti, 2002; Triandis, 1995). A high individualism reflects a preference to act independently (Tayeb, 1988), whereas high collectivism reflects a preference to work with others (Brock, 2005; Robert & Wasti, 2002). Individualists think in a term of ‘I’, while collectivists think in a term of ‘we’ (Hofstede, 1991). Moreover, a high H-IDV also reflects freedom, autonomy, privacy and performance based on evaluation (Brock, 2005; Hofstede, 1983; Tayeb, 1988; Very et al., 1996), while a low H-IDV reflects coordination within groups (Very et al., 1996). Besides, the planning in a low H-IDV context is supposed to be comprehensive, with neither strong resistance nor innovation (Brock et al., 2000), while it is expected that employees will make sacrifices for the common good of the organisation (Brock et al., 2000). Hence, an individualist society prizes personal control, autonomy, and individual accomplishments, while a collectivist society puts emphasis on loyalty and cohesion alongside imposes mutual obligations related to in-groups (Kyriacou, 2016).

Considering the outlined above, a low H-IDV (collectivism) should help with the coordination of operations and activities during the M&A process, which is supposed to help to pass smoothly the integration. However, employees with a collectivist view are more negatively affected by the perception of job insecurity and worsening working conditions (Oyserman et al., 2002; Probst & Lawler, 2006). Therefore, an organisation with a collectivist view is expected to defend the employees’ interests (Brock et al., 2000), which may hinder the ability to gain profitability because less layoff is expected during the integration. Besides, in a low H-IDV (collectivism), subordinates cannot easily shift between groups (Brock, 2005; Hofstede, 1991), which may negatively affect profitability because of the lack of transferring of knowledge and human resources between units and operations to remove redundancies and seize synergy potential. Conversely, individualist behaviour is characterised by a greater emphasis on managerial aspirations of leadership and greater encouragement of individual initiative (Brock, 2005; Hofstede, 1980a, 1983; Tayeb, 1988; Very et al., 1996). Hence, individualistic behaviour is more influenced by cost-benefit analysis, while putting a greater emphasis on autonomy and task variety (Probst & Lawler, 2006), which may raise more conflicts on how to carry out the integration.

Hypothesis 2: A higher IDV has a positive effect on profitability but has a negative effect on revenue between the pre-M&A period and the post-M&A period.

Hofstede-Uncertainty Avoidance Index (H-UAI). H-UAI is related to the level of stress in a society when facing an unknown future (Hofstede, 1983, 2011). It is also related to uncomfortable feelings in unstructured situations (Hofstede, 1983, 2011). Besides, H-UAI is related to rules orientation, employment stability and nervousness/stress at work (Hofstede, 1980b, 1983; Rapp et al., 2010). A high H-UAI reflects strict behavioural codes, laws and rules, as well as disapproval of deviant opinions and beliefs in absolute truth, while a low H-UAI reflects the tolerance of diverse opinions and fewer rules without an expectation to express emotions (Hofstede, 1983, 2011).

Considering the outlined above, one of the main implications of H-UAI in M&As is related to how the management has formed the integration planning, namely the ability to deal systematically with a tolerance of uncertainty (Brock et al., 2000). More importantly, H-UAI reflects the risk in entry to M&A deals, thereby, CEOs from high H-UAI countries less engage in M&As, while CEOs from low H-UAI countries more engage in large takeovers (Frijns et al., 2013). Furthermore, organisations with a low H-UAI favour immediate business activity (Brock et al., 2000), which results in simple, short-term, flexible planning (Brock et al., 2000). That may help to shorten the integration stage and gain short-term profits, but at the same time, it may lead to more risks and ‘surprise’ obstacles. However, a high H-UAI culture invests significant resources into planning (Brock et al., 2000), which may help to pass more smoothly the integration stage without “surprises”. Yet, strict planning to reduce risks may increase the costs of the integration stage, resulting in lower profitability. Nevertheless, organisations with a high H-UAI prefer structuring of activities, hiring experts, use of advanced technology and standardisation within the organisation (Brock et al., 2000; Hofstede, 1980a, 1983), which may help to maximise the synergy potential.

Hypothesis 3: A higher UAI has a positive effect on revenue but has a negative effect on profitability between the pre-M&A period and the post-M&A period.

Hofstede-Masculinity versus Femininity Index (H-MAS). H-MAS is related to the division of emotional roles between women and men and for the distribution of values between the genders (Hofstede, 1983, 1998, 2011). A high H-MAS reflects a high valuation of assertiveness and competitiveness, while a low H-MAS reflects an orientation toward people, quality and stability (Brock et al., 2000; Hofstede, 1983, 1998, 2011). Thereby, a high H-MAS reflects an admiration for the strong, while a low H-MAS reflects sympathy for the weak (Hofstede, 1983, 1998, 2011). Moreover, a high H-MAS culture tends to be oriented toward tasks, quantity and growth alongside favouring of planning processes that are top-down, programmed and inflexible (Hofstede, 1980a, 1983, 2011), which are supposed to contribute to profitability. However, a low H-MAS culture would favour planning that represents a more consultative, bottom-up process with a comprehensive consideration of internal know-how (Brock et al., 2000; Hofstede, 1983). Furthermore, a high H-MAS reflects hard work over family, while a low H-MAS reflects a balance between family and work (Hofstede, 1983, 1998, 2011).

In light of the above, H-MAS has a mixed effect regarding M&A performance. A low H-MAS is more likely to lead to synergies between the combined firms (Brock et al., 2000), but at the same time, a low H-MAS may increase the cost of employees due to the better working conditions, resulting in lower profitability. However, a high MAS is expected to increase firm profits due to the ‘hard work’ of the employees.

Hypothesis 4: A higher MAS has a positive effect on profitability but has a negative effect on revenue between the pre-M&A period and the post-M&A period.

Hofstede-Long-Term versus Short-Term Orientation (H-LTO). H-LTO reflects the differences between societies that put emphasis on the past through protecting the traditions, keeping social obligations to preserve personal steadiness and stability, and societies that put emphasis on the future through adaption to changing upon circumstances alongside hard-working to achieve future goals (Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005; Hofstede et al., 2010; Venaik et al., 2013).

A low H-LTO (short-term) societies more tend to spend on social activity and consumption, rather than securing future finance (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005)., which may hinder economic growth (Hofstede, 2011), and even may end in financial crisis and poor situation. In contrast, a high H-LTO (long-term) societies tend to secure the future through large savings and funds for investment (Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005), which encourage economic growth (Hofstede, 2011) or at least help to keep the economic stability with more ability to handle ‘rainy days’. Moreover, short-term orientation cultures have difficulties to adapt changes (Hofstede, 2011), which may hinder adaptions to new situations or new technologies or new products or even integrate foreigners within society. However, long-term orientation cultures open to foreign cultures with the ability to adapt to new circumstances, new processes, new technologies and such. At low H-LTO (short-term) orientation societies, failures and success explain by luck (Hofstede, 2011) or even destiny, so in case of failure, guilty feelings may not arise. However, in high H-LTO (long-term) orientation societies, failures and success are explained through hard work, or vice versa, due to lack of efforts, which leads to shame in case of failure (Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

In the light of the above, H-LTO may influence particularly the integration success because of the need to adapt organisational change alongside cutting costs and cutting jobs and activities to remove redundancies (Rozen-Bakher, 2018a). Hence, in case of a low H-LTO (short-term) orientation, less expected adaption to the integration with opposition to cutting jobs and costs, which may end in a failure of M&A. In other words, past orientation places primary emphasis on maintenance and restoration, rather than on shaping the future (Venaik et al., 2013). However, in the case of high H-LTO (long-term) orientation, the integration stage is supposed to pass more smoothly, because high H-LTO members using harmonious and cooperative facework strategies (Merkin, 2004) alongside adapting to the new organization after the merger, which may lead to M&A success. Nevertheless, Hofstede (2001) argued that businesses in long-term orientation cultures are working toward building up strong positions in their markets, so they do not expect immediate results. That is may lead to a trade-off between revenue and profitability because businesses with a long-term orientation may put on the line their profitability in order to increase their revenue in the long-term. In other words, the goal to increase the firm revenue may be achieved through avoiding cutting costs and jobs during the integration, which may result in increasing the revenue, but at the same time, it may hinder the profitability. Even the planning of the M&A may be influenced by the H-LTO. Thus, a high H-LTO (long-term) is supposed to improve the readiness for the integration, while a low H-LTO (short-term) orientation may keep their faith in luck, rather than on strict planning.

Hypothesis 5: A higher H-LTO has a positive effect on revenue but has a negative effect on profitability between the pre-M&A period and the post-M&A period.

To summarise, the study presents five hypotheses to examine the impact of national culture on M&A performance, as shown in Table 1 that summarises the theoretical background of the study. Four hypotheses H2-H5 (H-IDV, H-UAI, H-MAS and H-LTO) assume that exists a trade-off between the revenue and profitability during the M&A process (Rozen-Bakher, 2018c), while only hypothesis H1 (H-PDI) assumes a negative impact on both the revenue and profitability.

Methodology

The sample of the study includes 190 Buyers and 190 Sellers that were involved in M&A deals from 11 countries, as shown in Table 2. All the firms included in the sample have traded on the stock exchanges in the USA, both Buyers and Sellers. The study used the accounting research method that is based on analysing annual reports (10K) (Rozen-Bakher, 2018a). Annual reports (10K) are required by the USA Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (SEC, 2009; Rozen-Bakher, 2018d), so the public has free access to these annual reports. The study examined the M&A process through the change in the M&A performance between the Pre-M&A period and the Post-M&A period (Kubo & Saito, 2012; Rozen-Bakher, 2018a, 2018d). Hence, the Pre-M&A period is based on the last annual reports (10k) of the buyer and the seller before the M&A took place, while the Post-M&A period is based on the annual report of the buyer after the M&A that is already included in the annual report of the seller.

Table 3 presents the variables of the study. First, the study measures the national culture of the Buyer and the Seller as independent variables through the six cultural dimensions of Hofstede (Hofstede, 2011), as well as through the nine cultural dimensions of Globe (House et al., 2002; House et al., 2004). Second, the study includes M&A performance as the dependent variable of the study through two prominent indicators of firm performance, namely the revenue and the net profit (Declerck, 2003; Gates & Very, 2003; Reddy et al., 2012; Rozen-Bakher, 2018a, 2018e; Zollo & Meier, 2008). Third, the study includes five control variables that represent the performances and characterises of the Buyer and Seller in the pre-M&A period (Kemal, 2011; Rozen-Bakher, 2018a, 2018c), as well as the sector related between the Buyer and Seller.

Results

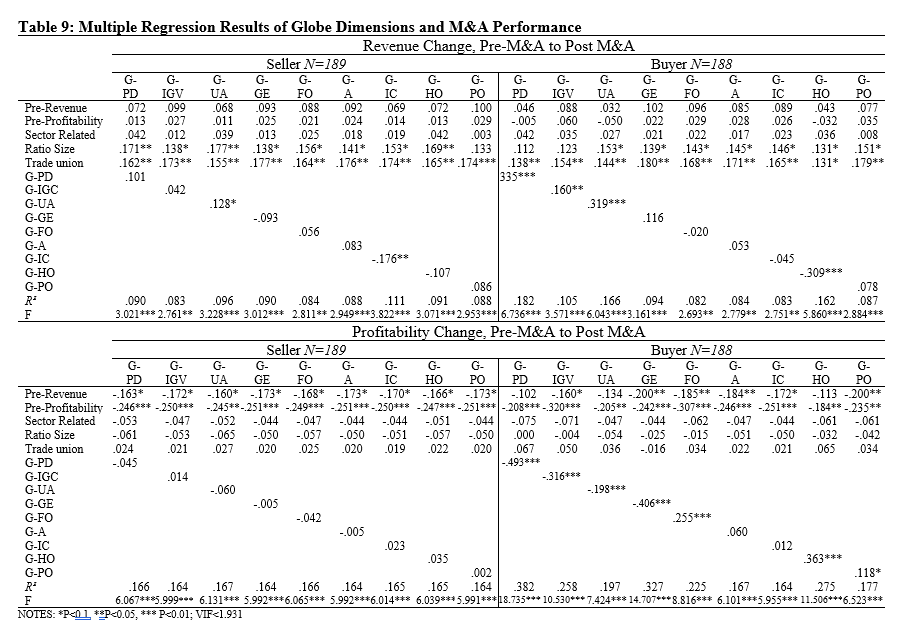

Tables 4–10 show the study results. Table 4 shows the means and descriptive statistics of the research variables. Table 5 shows the correlation matrix between the research variables and Hofstede dimensions, while Table 6 shows the correlation matrix between the research variables and Globe dimensions. Nevertheless, Table 7 shows the correlations between Hofstede dimensions and Globe Dimensions, which partially confirm the theoretical similarity between Hofstede and Globe frameworks, yet with significant differences between the Buyer and Seller, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 8 shows the multiple regression results of Hofstede dimensions and M&A performance, while Table 9 shows the multiple regression results of Globe dimensions and M&A performance. The results of the Buyer confirm H2, H3, H4 and H5 but partially support H1, while the results of the Seller only partially confirm H3 and H5 but do not support H1, H2 and H4, as shown in Table 11 that summarises the significant results of the study. The results of the Buyer show that a higher H-PDI, a higher H-UAI and a higher H-LTO are significantly and positively associated with the revenue, but at the same time, they are significantly and negatively associated with profitability. The results of the Buyer also show that a higher H-IDV and a higher H-MAS are significantly and negatively associated with the revenue, but at the same time, they are significantly and positively associated with the profitability. However, the results of the Seller show that only a higher H-UAI and a higher H-LTO are significantly and positively associated with the revenue, while H-PDI, H-IDV and H-MAS of the seller show no significant results, still, a high H-IVR as a control dimension shows significantly and negatively associated with the revenue. Nevertheless, the comparison between Hofstede and Globe shows that only G-IGC shows similar results with H-IDV, while G-FO shows partial similarity results with H-MAS regarding the profitability, but the other Globe dimensions show different results compared to Hofstede dimensions, as shown in Table 11.

Table 10 shows the last step of the stepwise multiple regression to identify the dominant cultural dimensions among Hofstede framework, as well as among the cultural dimensions of Globe. The results show that H-PDI, H-IDV and H-IVR more predict M&A success among Hofstede dimensions, while G-PD, G-GE, G-A, G-IC and G-PO more predict M&A success among Globe dimensions, still, both frameworks, Hofstede and Globe, show that the national culture of the Buyer more predicts M&A success compared to the national culture of the Seller.

Discussion

The analysis of the study highlights the pioneering of this research. The study reveals a surprising finding that the national culture of the Buyer more predicts M&A success compared to the national culture of the Seller, which is contradicted the ‘due-diligence’ rationale. More importantly, that may explain the contradiction between the results of previous studies regarding cultural distance. Cultural distance assumes that the differences in national culture between the Buyer and the Seller affect M&A success. However, according to this study, if the Buyer more predicts M&A success compared to the Seller, then a cultural distance with an equal-weighted index cannot use as a predictor for M&A success. In other words, it is correct to use a difference between two factors when both of them are supposed to influence equally on the outcome. However, in case that one factor is significantly dominant compared to the second one, then examining the difference between the two factors may produce inaccurate results, especially in the case of using an equal-weighted index between the two factors instead of using not equal weight or even using only the dominant factor. Considering that, the testing of the cultural distance in the current literature that based on an equal-weighted index between the Buyer and Seller (e.g. composite index of Kogut & Singh, 1988) instead of using unequal weight or even testing it separately as done in this research. Thereby, the testing of equal-weighted indexes between the Buyer and the Seller may explain the mixed results in the current literature.

Nevertheless, at the theoretical level, future studies should explore in-depth the reasoning for the dominance of the national culture of the Buyer compared to the national culture of the Seller in predicting M&A success. It may be explained by the dominant role of the Buyer in the decision-making during the integration. However, it may be also explained by the trying of the Buyer to impose its national culture on the Seller, especially when the Buyer implements a global strategy of standardisation in its all subsidiaries in host countries (Ang & Massingham, 2007). Under this unified global strategy, the national culture of the Buyer more impacts the M&A success of the Buyer worldwide compared to the national culture of Seller in a certain host country.

The study also brings to light the trade-off that exists in M&A strategy (Rozen-Bakher, 2018c), namely the trade-off between the revenue and the profitability, as shown in Table 11. The results show that all the six cultural dimensions of Hofstede lead to a trade-off between revenue and profitability, which may confirm the argument that a trade-off between the indicators of M&A performance may explain the high failure rate of M&A strategy (Rozen-Bakher, 2018c).

Conclusions

Due to the mixed results of cultural distance (e.g. Bauer et al., 2016; Bauer & Matzler, 2014; Boateng et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2016; Rozen-Bakher, 2018b; Sarala, 2010; Stahl & Voigt, 2008; Vaara et al., 2014) along with the unexplained of the high failure rate of M&A strategy in the current literature (King et al., 2004; Kumar & Sharma, 2019; Matsumoto, 2019; Renneboog & Vansteenkiste, 2019; Rozen-Bakher, 2018a, 2018c; Sarala, 2010; Steger & Kummer, 2007; Tichy, 2001; Venema, 2015; Thelisson, 2020; Weber et al., 2012), this study takes a different approach by examining if the national culture of the Buyer compared to the national culture of the Seller may explain the unresolve risk of national culture when M&A strategy is implemented. In other words, this study investigates if analysis of the national culture of the Buyer versus the Seller instead of analysis of the cultural distance between the Seller and the Buyer may explain the contradiction results of cultural distance among previous studies.

To accomplish this goal, the study used the Hofstede framework, as well as the Globe as a Control Framework, with the aim of getting a clearer understanding about IF and HOW the national culture of the Buyer versus the Seller predict M&A success. The study also tried to determine who more dominant in predicting M&A success, the national culture of the Seller or the national culture of the Buyer. The study used the accounting research method by analysing annual reports (10K) of 190 Sellers and 190 Buyers from 11 countries.

The results of the study reveal that the national culture of the Buyer more impacts M&A success compared to the national culture of the Seller. The study also indicates that exists a trade-off between the revenue and the profitability regarding the six cultural dimensions of Hofstede, which may explain the high failure rate of M&A strategy (Rozen-Bakher, 2018c). The study even reveals that Hofstede and Globe Frameworks have positive similarities in relation to only three cultural dimensions, namely H-PDI/G-PD and H-UAI/G-UA of the Buyer, while H-LTO/G-FO of the Seller. To conclude, the study indicates that H-PDI and H-IDV of the Buyer more predict M&A success compared to other Hofstede dimensions.

Theoretical and Managerial Implications

The theoretical implications of the study mainly arise due to the finding of the study that the Buyer is more dominant in predicting M&A success over the Seller. Hence, the study analysis challenges the use of cultural distance with equal-weighted indexes between the Buyer and the Seller because of the dominance of the Buyer over the Seller. Thus, theoretical studies should explore the use of cultural distance with unequal-weighted indexes between the Buyer and the Seller. Besides, the dominance of the Buyer may signal that the current ‘due-diligence’ thinking that mainly focuses on the Seller to predict M&A success may explain the failure of countless deals. Thus, theoretical studies should doubt the current ‘due-diligence’'s grounds in order to find a new approach on how to implement ‘due-diligence’ that will take into account the dominance of the Buyer to predict M&A success.

The study also has two important managerial implications. First, the study does not confirm the common thinking that the Seller more predicts the success of the deal compared to the Buyer. Thereby, the ‘due-diligence’ should focus not only on the Seller or on the fit between the buyer and the Seller but also on the Buyer to predict M&A success. Second, the study reveals which combinations of cultural dimensions have the potential to lead to M&A success, or vice versa, to M&A failure. Hence, a combination of a high H-PDI, a high H-UAI and a high H-LTO of the Buyer may maximize the revenue, while a combination of a high H-IDV and a high H-MAS of the buyer may maximize the profitability. However, a combination of a high H-UAI and a high H-LTO of the Seller may maximize the revenue. Nevertheless, a combination of a high H- PDI, a high H-UAI and a high H-LTO of the buyer may lead to lower profits, while a combination of a high H-IDV and a high H-MAS of the buyer may lead to lower revenue.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research

This study emphasises the need for future studies due to the limitations of this study, as follows. First, following the criticism in the literature regarding neither Hofstede (Shenkar, 2001) or Globe (House et al., 2006) frameworks, then future studies should explore alternative factors for national culture/cultural distance in M&As, such as language distance (Konara & Wei, 2014), religion distance (Helble, 2007) and Cultural Openness vs. ethnocentrism (Altintas & Tokol, 2007). Second, this study used the accounting method for its database, so future research should examine the research model of this study by using different research methods (Cartwright et al., 2012). Third, the sample of this study includes only Western countries, so future studies should investigate the research model of this study by using samples from Eastern countries. Finally, future studies should explore additional control variables that do not include in this study, such as types of M&A (Rozen-Bakher, 2018a), certain sectors and more.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour.

Alipour, A. (2019). The conceptual difference really matters: Hofstede vs GLOBE’s uncertainty avoidance and the risk-taking behavior of firms. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 26(4), 467-489.

Altintas, M.H. & T Tokol, T. (2007). Cultural openness and consumer ethnocentrism: an empirical analysis of Turkish consumers. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 25 (4), 308-325.

Ang, Z., & Massingham, P. (2007). National culture and the standardization versus adaptation of knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management,11(2), 5-21.

Angwin, D., & Savill, B. (1997). Strategic perspectives on European cross-border acquisitions: A view from top European executives. European Management Journal, 15, 423–435.

Bailey, N., & Li, S. (2015). Cross-national distance and FDI: the moderating role of host country local demand. Journal of International Management, 21(4), 267-276.

Barkema, H. G., Bell, J. H., & Pennings, J. M. (1996). Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strategic management journal, 17(2), 151-166.

Bauer, F., & Matzler, K. (2014). Antecedents of M&A success: The role of strategic complementarity, cultural fit, and degree and speed of integration. Strategic management journal,35(2), 269-291.

Bauer, F., Matzler, K., & Wolf, S. (2016). M&A and innovation: The role of integration and cultural differences—A central European sellers perspective. International Business Review,25(1), 76-86.

Boateng, A., Du, M., Bi, X., & Lodorfos, G. (2019). Cultural distance and value creation of cross-border M&A: The moderating role of acquirer characteristics. International Review of Financial Analysis, 63, 285-295.

Benito, G.R., & Gripsrud, G. (1992). The expansion of foreign direct investments: discrete rational location choices or a cultural learning process? Journal of International Business Studies, 23, 461–476.

Brock, D. M. (2005). Multinational acquisition integration: the role of national culture in creating synergies. International Business Review,14(3), 269-288.

Brock, D. M., Barry, D., & Thomas, D. C. (2000). “Your forward is our reverse, your right, our wrong”: rethinking multinational planning processes in light of national culture. International Business Review,9(6), 687-701.

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., Greenberg, J., Gelfand, M. J., Francesco, A. M., Chen, Z. X., ... & Shapiro, D. (2001). Culture and procedural justice: The influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,37(4), 300-315.

Brouthers, K. D., & Brouthers, L. E. (2001). Explaining the national cultural distance paradox. Journal of International Business Studies,32(1), 177-189.

Bruner, R. (2004). Applied Mergers & Acquisitions. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cartwright, S., Teerikangas, S., Rouzies, A., & Wilson-Evered, E. (2012). Methods in M&A—A look at the past and the future to forge a path forward. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 28(2), 95-106.

Chhokar, J. S., Brodbeck, F. C., & House, R. J. (Eds.). (2007). Culture and leadership across the world: The GLOBE book of in-depth studies of 25 societies. Routledge.

Declerck, F. (2003). Valuation of seller firms acquired in the food sector during the 1996-2001 wave. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review,5(4), 1-16.

Evans, J., & Mavondo, F. T. (2002). Psychic distance and organizational performance: An empirical examination of international retailing operations. Journal of international business studies,33(3), 515-532.

Frijns, B., Gilbert, A., Lehnert, T., & Tourani-Rad, A. (2013). Uncertainty avoidance, risk tolerance and corporate takeover decisions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(7), 2457-2471.

Gates, S., & Very, P. (2003). Measuring performance during M&A integration. Long Range Planning,36(2), 167-185.

Gelfand, M. J., Erez, M., & Aycan, Z. (2007). Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 58, 479-514.

Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Palich, L. E. (1997). Cultural diversity and the performance of multinational firms. Journal of International Business Studies,28(2), 309-335.

Helble, M. (2007). Is God good for trade?. Kyklos, 60(3), 385-413.

Hofstede, G. (1980a). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization,10(4), 15-41.

Hofstede, G. (1980b). Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Hofstede, G. (1983). National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management & Organization,13(1-2), 46-74.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind. London: McGraw‐Hill.

Hofstede, G. (1993). cultural constraints in management theories. Academy of Management Executive, 7 (1), 81-94.

Hofstede, G. (Ed.). (1998). Masculinity and femininity: The taboo dimension of national cultures (Vol. 3). Sage Publications. (Chapter I)

Hofstede, G. (2001). Cultures consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online readings in psychology and culture,2(1), 8.

Hofstede, G. & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (Rev. 2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J. & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (Rev. 3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

House, R. J. (2001). Lessons from project GLOBE. Organizational dynamics, 29(4), 289-305.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage publications.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Dickson, M., & Gupta, V. (1999). Cultural influences on leadership and organizations: Project GLOBE. Advances in global leadership, 1(2), 171-233.

House, R. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Sully de Luque, M. (2006). A failure of scholarship: Response to George Graen's critique of GLOBE. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(4), 102-114.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: an introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of world business, 37(1), 3-10.

Huang, Z., Zhu, H.S., & Brass, D.J. (2017). Cross-border acquisitions and the asymmetric effect of power distance value difference on long-term post-acquisition performance. Strategic Management Journal, 38, 972–991.

Jalalkamali, M., Ali, A. J., Hyun, S. S., & Nikbin, D. (2016). Relationships between work values, communication satisfaction, and employee job performance: The case of international joint ventures in Iran. Management Decision, 54(4), 796-814.

Kayalvizhi, P. N., & Thenmozhi, M. (2018). Does quality of innovation, culture and governance drive FDI?: Evidence from emerging markets. Emerging Markets Review, 34, 175-191.

Kemal, M. U. (2011). Post-merger profitability: A case of Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS). International Journal of Business and Social Science,2(5), 157-162.

Khatri, N. (2009). Consequences of power distance orientation in organisations. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective,13(1), 1-9.

King, D. R., Dalton, D. R., Daily, C. M., & Covin, J. G. (2004). Meta‐analyses of post‐acquisition performance: Indications of unidentified moderators. Strategic management journal,25(2), 187-200.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of international business studies,19(3), 411-432.

Konara, P., & Wei, Y. (2014). The Role of Language in Bilateral FDI: A Forgotten Factor?. In International Business and Institutions after the Financial Crisis (pp. 212-227). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Kubo, K., & Saito, T. (2012). The effect of mergers on employment and wages: Evidence from Japan. Journal of The Japanese and International Economies,26, 263-284.

Kumar, V., & Sharma, P. (2019). Why Mergers and Acquisitions Fail?. In An Insight into Mergers and Acquisitions (pp. 183-195). Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Kyriacou, A. P. (2016). Individualism–collectivism, governance and economic development. European Journal of Political Economy, 42, 91-104.

Lajoux, A. R., & Elson, C. M. (2000). The Art of M&A Due Diligence. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Li, J & Guisinger, S. (1992). The globalization of service multinationals in the 'triad' regions- Japan, Western Europe and North America. Journal of International Business Studies, 23 (4), 675-696.

Lim, J., Makhija, A. K., & Shenkar, O. (2016). The asymmetric relationship between national cultural distance and seller premiums in cross-border M&A. Journal of Corporate Finance,41, 542-571.

Lincoln, J. R., Hanada, M., & Olson, J. (1981). Cultural orientations and individual reactions to organizations: A study of employees of Japanese-owned firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 93-115.

Loree, D. & Guisinger, S. (1995). Policy and Non-Policy determinants of US foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 26 (2), 281-299.

Matsumoto, S. (2019). The Causes of Failure: Case Studies of Eight Failed Acquisitions Ending in a Sale or Withdrawal at a Loss. In Japanese Outbound Acquisitions (pp. 65-105). Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Merkin, R. S. (2004). Cultural long-term orientation and facework strategies. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 12(3), 163-176.

Morosini, P., Shane, S., & Singh, H. (1998). National cultural distance and cross-border acquisition performance. Journal of international business studies,29(1), 137-158.

Norburn, D., & Schoenberg, R. (1994). European cross-border acquisition: how was it for you?. Long Range Planning, 27, 25 –34.

Olie, R. (1990). Culture and integration problems in international mergers and acquisitions. European Management Journal, 8, 206–215

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. 2002. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin,128(1), 3-72.

Perry, J. S. & Herd, T. J. (2004). Mergers and acquisitions: Reducing M&A risk through improved due diligence. Strategy and Leadership, 32 (2): 12-19.

Prendergast, C. (1993). A theory of "yes men". The American Economic Review, 757-770.

Probst, T. M., & Lawler, J. (2006). Cultural values as moderators of employee reactions to job insecurity: The role of individualism and collectivism. Applied Psychology,55(2), 234-254.

Puranam, P., Powell, B. C., & Singh, H. (2006). Due diligence failure as a signal detection problem. Strategic Organization, 4(4), 319-348.

Rapp, J. K., Bernardi, R. A., & Bosco, S. M. (2010). Examining the use of Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance construct in international research: A 25-year review. International Business Research,4(1), 3.

Reddy, K. S., Nangia, V. K., & Agrawal, R. (2012). Mysterious broken cross-country M&A deal: Bharti Airtel-MTN. Journal of the International Academy for Case Studies,18(7), 61-75.

Renneboog, L., & Vansteenkiste, C. (2019). Failure and success in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 58, 650-699.

Robert, C., & Wasti, S. A. (2002). Organizational individualism and collectivism: Theoretical development and an empirical test of a measure. Journal of Management,28(4), 544-566.

Rozen-Bakher, Z. (2018a). Comparison of Merger and Acquisition (M&A) Success in Horizontal, Vertical and Conglomerate M&As: Industry Sector vs. Services Sector. The Service Industries Journal, 38(7-8), 492-518. DOI: 10.1080/02642069.2017.1405938

Rozen-Bakher, Z. (2018b). How the National Cultural Differences Influence M&A Success in Cross-Border M&As?. Transnational Corporations Review,10(2): 131-146. DOI:10.1080/19186444.2018.1475089

Rozen-Bakher, Z. (2018c). The Trade-off Between Synergy Success and Efficiency Gains in M&A Strategy. EuroMed Journal of Business,13(2), 163-184. DOI: 10.1108/EMJB-07-2017-0026

Rozen-Bakher, Z. (2018d). Labour Productivity in M&As: Industry Sector vs. Services Sector. The Service Industries Journal, 38(15-16), 1043-1066. DOI: 10.1080/02642069.2017.1397136

Rozen-Bakher, Z. (2018e). Could the pre-M&A performances predict integration risk in cross-border M&As?. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26(4), 652-668.

Sarala, R. M. (2010). The impact of cultural differences and acculturation factors on post-acquisition conflict. Scandinavian Journal of Management,26(1), 38-56.

Sarala, R. M., & Vaara, E. (2010). Cultural differences, convergence, and crossvergence as explanations of knowledge transfer in international acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(8), 1365-1390.

SEC. (2009). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. https://www.sec.gov/fast-answers/answers-form10khtm.html Last modified: June 26, 2009.

Sent, E. M., & Kroese, A. L. (2020). Commemorating Geert Hofstede, a pioneer in the study of culture and institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 1-13.

Shenkar, O. (2001). Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of international business studies,32(3), 519-535.

Shi, X., & Wang, J. (2011). Interpreting Hofstede model and GLOBE model: which way to go for cross-cultural research?. International journal of business and management, 6(5), 93.

Slangen, A. H. (2006). National cultural distance and initial foreign acquisition performance: The moderating effect of integration. Journal of World Business,41(2), 161-170.

Stahl, G. K., & Voigt, A. (2008). Do cultural differences matter in mergers and acquisitions? A tentative model and examination. Organization Science, 19(1), 160-176.

Steger, U., & Kummer, C. (2007). Why merger and acquisition (M&A) waves reoccur: the vicious circle from pressure to failure. IMD.

Tang, L. (2012). The direction of cultural distance on FDI: attractiveness or incongruity?. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 19(2), 233-256.

Tayeb, M. H. (1988). Organizations and national culture: A comparative analysis. London: Sage.

Teerikangas, S., & Very, P. (2006). The culture–performance relationship in M&A: From yes/no to how. British journal of management, 17(S1), S31-S48.

Thelisson, A. S. (2020). Managing failure in the merger process: evidence from a case study. Journal of Business Strategy.

Thomas, D.E. & Grosse, R. (2001). Country-of-origin determinants of foreign direct investment in an emerging market: the case of Mexico. Journal of International Management, 7(1): 59–79.

Tichy, G. (2001). What do we know about success and failure of mergers?. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade,1(4), 347-394

Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and social behavior. London: McGraw-Hill.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Boulder, CO, US: Westview Press

Tsui, A. S., Nifadkar, S. S., & Ou, A. Y. (2007). Cross-national, cross-cultural organizational behavior research: Advances, gaps, and recommendations. Journal of management, 33(3), 426-478.

Tung, R. L., & Verbeke, A. (2010). Beyond Hofstede and GLOBE: Improving the quality of cross-cultural research.

Vaara, E. (2003). Post-acquisition integration as sensemaking: glimpses of ambiguity, confusion, hypocrisy, and politicization. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 859–894.

Vaara, E., Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Ehrnrooth, M., & Koveshnikov, A. (2014). Attributional tendencies in cultural explanations of M&A performance. Strategic Management Journal,35(9), 1302-1317.

Venaik, S., Zhu, Y., & Brewer, P. (2013). Looking into the future: Hofstede long term orientation versus GLOBE future orientation. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal.

Venema, W. H. (2015). Integration: The Critical M&A Success Factor. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance,26(4), 23-27.

Very, P., Calori, R., & Lubatkin, M. (1993). An investigation of national and organizational cultural influences in recent European mergers. Advances in strategic management,9, 323-346.

Very, P., Lubatkin, M., & Calori, R. (1996). A cross-national assessment of acculturative stress in recent European mergers. International Studies of Management & Organization,26(1), 59-86.

Very, P., Lubatkin, M., Calori, R., & Veiga, J. (1997). Relative standing and the performance of recently acquired European firms. Strategic management journal, 593-614.

Waldman, D. A., De Luque, M. S., Washburn, N., House, R. J., Adetoun, B., Barrasa, A., ... & Dorfman, P. (2006). Cultural and leadership predictors of corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 823-837.

Weber, Y., Shenkar, O., & Raveh, A. (1996). National and corporate cultural fit in mergers/acquisitions: An exploratory study. Management science, 42(8), 1215-1227.

Weber, Y., Tarba, S. Y., & Rozen-Bachar, Z. (2012). The effects of culture clash on international mergers in the high tech industry. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development,8(1), 103-118.

Xiumei, S. H. I., & Jinying, W. A. N. G. (2011). Cultural distance between China and US across GLOBE model and Hofstede model. International Business and Management, 2(1), 11-17.

Zaheer, S. (1995) Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal,38(2), 341-363.

Zhou, Y., & Kwon, J. W. (2020). Overview of Hofstede-Inspired Research Over the Past 40 Years: The Network Diversity Perspective. SAGE Open, 10(3), 2158244020947425.

Zollo, M., & Meier, D. (2008). What is M&A performance?. The Academy of Management Perspectives,22(3), 55-77.